采访:Dawei Interview, Part II (诗人)

By Josh, 2015年 12月 24日

《 中文采访在豆瓣音乐 》

Rogue historian, madcap rapper; wushu shifu, battle master. Dawei is a major paradox in a small package, a true poet provocateur. With his lyrically complex, often openly political songs and poems, Dawei remains a witting pariah on the outskirts of the Beijing hip hop underground, rejecting mainstream fame, wealth, and stability in an unflinching commitment to truth and purity in his art. Self-deprecating while self-aggrandizing, he’s the epitome of and antithesis to any MC stereotype.

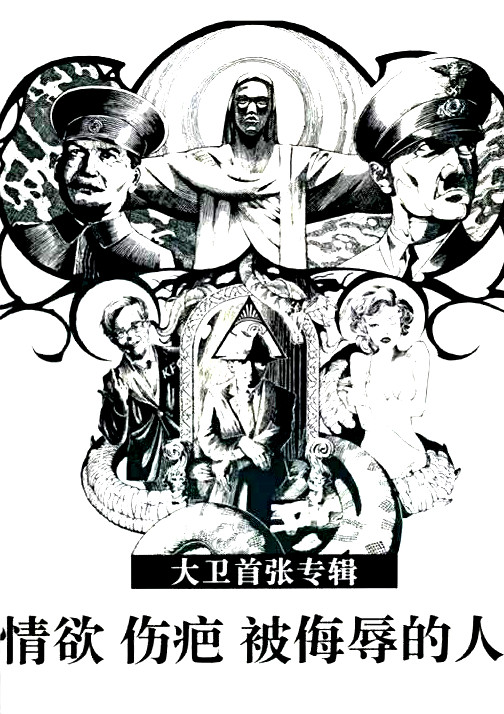

Dawei has just released his first major work: Lust, Scars, The Insulted Man, a psycho-libidinal, alt-historical parable comprising the young artist’s worldview in sound (CD), image (DVD), and word (poetry book). In this three-part profile, we explore three faces of Dawei: the madman (狂人), the ruthless battle MC and martial artist; the poet (诗人), the artist as philosopher; and the lover (情人), a figure fusing the personal with the universal, the times with the timeless.

Part II: 诗人* delves into Dawei’s philosophy of art and poetry, his self-guided study of history and society, and the obstacles he faces as an artist consciously testing the limits of State censors and music industry wonks…

photo by Laurent Hou

1. In School

pangbianr: How did you balance your extracurriculars — MC battling and martial arts — with your school work? Did you do well in school?

Dawei: During high school, on weekends I would go out and become this rapper, this battle king. Everyone would say I was the rapper in Beijing with the most potential. But on weekdays, I had to sit in class and listen to the teachers lecture me, go into the cafeteria and listen to my classmates talk about how they need more veggies in their lunch meals, all while I’m listening to a Wu Tang beat, secretly practicing freestyling. That really tore me apart, I felt like I didn’t belong at all. I didn’t even care to show off or tell my classmates about my achievements outside school. I just didn’t care. I basically didn’t talk in high school.

Then in the last year of high school I had to face gaokao. I still went to a freestyle battle in June that year, which drove my dad crazy. I sat down with him at the time, told him that I didn’t want to take gaokao, didn’t want to be with my peers, didn’t want to go to university. But my dad said, “No, you’re a fighter. A fighter has to go to war.” And I said, “Yes, but if I were an American soldier, and you put me in the North Korean military, that would make no sense. That’s not where I belong.” To this day, my dad still recalls this excellent analogy. [laughs]

pangbianr: Did you end up taking the gaokao?

Dawei: I did. I did well, actually. Don’t know how that happened.

pangbianr: Did you go to college?

Dawei: I gave it a try. I went to Beijing Union University [北京联合大学], took a few classes, then quit.

pangbianr: What was your major?

Dawei: For my first semester my major was Chinese Language and Culture. But there’s a thing in Chinese university called quantui [劝退], where the school advises you to drop out. They thought I wasn’t suitable. My dad asked me, “Do you not like this major?” And I said, “No, it’s the school that’s too stupid. Even if there was a Dragon Slaughtering major, they’d manage to make it boring.” But my dad insisted it was because of the major. So I switched to a History major for my second semester. And the same thing happened again. I was advised to drop out.

pangbianr: Why did think the school was stupid?

Dawei: The reason I told my dad it wasn’t the major, it was the school, was because sitting in any class, in any major, whatever they were teaching, the only thing that I could experience was bureaucracy. The school was the most evil, shameless link of the whole bureaucratic system. I could get nothing out of it other than the enforcement of bureaucratic ideology. A lot of people ask me why I dropped out, and I always say, “Because the school got in the way of my studies.” I never had, or have, any plan. I do very little planning. All I have is the confidence that I will eventually achieve my full self-expression. School got in the way of that, of my confidence, so I had to get rid of it.

2. Rogue Historian

pangbianr: So what did you do after school? Did you focus on hip hop? Did you study history on your own?

Dawei: Both happened simultaneously. The reason why I want to output my mind into hip hop is because I keep studying history. I need to study first, then put it into words through my hip hop work. It’s all organically connected.

pangbianr: Why do you care about history?

Dawei: What is history? History is often related to academia or ideology by most people. I see it differently. I believe that history is the process that makes us who we are today. Without learning history, we won’t get anything done, we won’t learn anything.

pangbianr: What made you realize that there was some other version outside of what you were being taught in school?

Dawei: It dates back to an after-school writing class, during middle school. One day the teacher seemed really sad, frustrated. During the class break he got into a personal conversation with me. He said: “I don’t understand why kids nowadays can only write articles that have absolutely no personal opinions.” Then he started to give me this really pessimistic idea. He was telling me, “Yeah, I guess that’s the way it is, looking at our history book, how it says the Communist Party kicked the Japanese out, how lihai [strong/fierce] they were.” And I said, “Yeah, they are lihai, aren’t they?” And the teacher said, “Why don’t you look it up yourself.”

pangbianr: How do you think about history now? What is the difference between the history you were taught in school and your own idea of history?

Dawei: The most important thing to any governing power is legality, legitimacy. And what matters most in determining legitimacy is history. History is the most important source of legality. Like George Orwell says in 1984, “Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.”

The ultimate demand of official history education is nothing but control, control, control. The characteristic of history education in China is to completely deny humanity. What I mean by “denying humanity” is denying complexity. Humans are very complicated. But in our history books, there’s only good and bad, those who should be killed and those who should be praised. The group in power has been writing history books the way they want, shaping the kids who are reading these history books. That follows the Orwell quote. This kind of history education turns today’s living people into historical figures from textbooks. Most Chinese people nowadays can only see people in the way the history books see people.

Recently a scholar of Han Chinese culture [汉学家] said, “The biggest problem with Chinese writers is that they don’t understand human beings.” History is the history of humanity. If you don’t truly understand history, then you don’t understand human beings. For the unofficial historical narrative, the ultimate demand is to answer the question: “How did we become who we are today?”

At the end of the day, it comes down to curiosity rather than control. It’s a willingness to embrace, to understand, to fathom the complexity of humanity. Looking at Chinese society today, it’s really violent. People are so scared of complexity. They refuse to understand anything complicated, they refuse to embrace the complexity in their nature. That is the result of our history education.

pangbianr: How do you approach this complexity that you feel is hidden in mainstream education or culture?

Dawei: The first step is to be completely honest and earnest. First we have to be honest with ourselves. If we do that, we see that a lot of things that we think and feel disgust us. We’re scared of it. So before truly understanding this complexity, we have to be honest and earnest with ourselves. First we face our own complexity, even if it’s dangerous.

3. Language, Censorship, and the Market

pangbianr: How do you introduce this kind of historical and personal complexity into your work?

Dawei: In my songs, you can always sense a kind of hopelessness. It’s not the kind of hopelessness that leads to self-destruction, but the kind of hopelessness in an old Chinese saying, 置之死地而后生: one must be near death to truly live. After this kind of rebirth, what comes with it is more hopelessness. Why does history repeat itself? Because human beings repeat themselves. Because people are self-aggrandizing. An artist as a human being cannot escape this fate of self-copying. What we can do as artists is to present this kind of self-repeating in a more beautiful way.

pangbianr: What themes do you wish to explore through your poetry and rap?

Dawei: Rather than themes that I want my writing to fit into, it’s more like my language will take me places. After I wrote my first song, “山中孙”, I got really frustrated. It’s not like the kind of frustration I got after my first attempt at freestyling. That kind of frustration contains some kind of self-mockery, like, “Oh, I can’t do this.” But the frustration I got out of writing my first song was deep, profound. It made me realize my language is so banal, I only have the language of daily life. And that’s when I started to enhance my language through reading so many books, through studying history.

And then I realized, language is so powerful that it doesn’t bow in front of a theme. Everything else bows in front of language. And that’s also my ideal artistic status. I realized that everything is created by language. You don’t create something first and then try to describe it with language. A lot of people, when they’re trying to write novels, or even poetry, they predetermine the theme and try to make the words go in that direction. But not for me. I devote all my faith, religiously, to language. I believe that as a good poet, you have to choose language as your primary religion.

pangbianr: How did you first put together a live set of your own material? What was the first time you ever performed outside of a battle context?

Dawei: I don’t remember the first time I started to perform my own songs. But the one thing that hasn’t changed is that whenever I perform, I always put several freestyle verses into the performance. It’s the freestyle spirit that carries me through my writing, my poetry, my history writing, and my song writing. I continue to freestyle to enhance my confidence to carry on the rest of the performance.

pangbianr: You said earlier that openly confronting personal complexity is “dangerous.” Since many of your songs are openly political, you often come into conflict with the government, or at least with censors. What kinds of “danger” do you encounter by pursuing your role as an artist in this way?

Dawei: Since I’ve been writing and performing my own material, I haven’t encountered danger as much as frustration. In this capitalist market, if you’re against the censorship system, they can stand in the way of the media. So you can’t even be on the market. Media is a product of capitalism, and the nature of capitalism is to seek profit. If you go against censorship, it forbids you from seeking profit.

For all these years, the media hasn’t had the guts to talk about me. I’m a long-term neglected character. So what I really get is frustration. This puts me in the most ancient, common, boring dilemma that artists have faced over thousands of years. It ensures that you turn into a one-man show. Over a long period of time, artists who lack confidence start to deny, to doubt their own work. And that is the biggest danger that censorship has brought to me. It’s nothing direct or violent.

pangbianr: You’ve just put out your book, CD, and DVD, and you’re very limited in how you can present them due to these censorship issues. What is your goal? What is your objective or hope in releasing these works?

Dawei: Whenever an artist talks about his “goals,” he’s already failed as an artist. Because to express yourself, to perform art, is art itself. You shouldn’t set any goals for it.

Publishing my book, releasing my record, these actions only destroy my animal-ness. It has nothing to do with my artistry, with my artistic achievements. I think if an artist says, “It makes me happy as long as I can sing my songs to myself in front of a mirror,” that’s total hypocrisy. As an artist you want some kind of fame. But if you say, “All the art I do is for these releases, for this goal,” that’s just shameless.

So my priority is going to forever be my expression, 100% expression. If my expression can affect some of the audience out there, then that’s great. But I will never compromise my work, my expression, for even 0.01% of the audience. Because if I have to play someone who I’m not to get any kind of fame, that will be the ultimate frustration.

***

Dawei has just released Lust, Scars, The Insulted Man, a box set containing a CD, a DVD of self-directed music videos, and a book of his poetry. Stream it here and buy it here. Read Part I of this interview here: Dawei Interview, Part I (狂人)

And tune in next week for Part III: Dawei, the Lover (情人).

*This interview was conducted in Chinese and translated to English by Emma Sun

awesome interview. keep up the good work man