采访:Dawei Interview, Part III (情人)

By Josh, 2016年 1月 26日

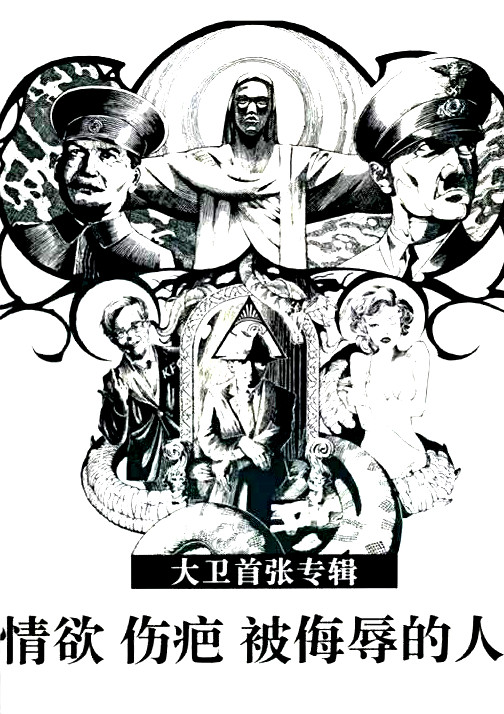

《 中文采访在豆瓣音乐 》

Rogue historian, madcap rapper; wushu shifu, battle master. Dawei is a major paradox in a small package, a true poet provocateur. With his lyrically complex, often openly political songs and poems, Dawei remains a witting pariah on the outskirts of the Beijing hip hop underground. He’s just released his first major work: Lust, Scars, The Insulted Man, a psycho-libidinal, alt-historical parable comprising the young artist’s worldview in sound (CD), image (DVD), and word (poetry book). To mark the occasion, we present Dawei in triple profile: the madman (狂人), the ruthless battle MC and martial artist; the poet (诗人), the artist as philosopher; and the lover (情人), a figure fusing the personal with the universal, the times with the timeless.

Part III: 情人 covers the overlap between Dawei the poet-historian and Dawei the emotional animal. On Lust, Scars, The Insulted Man, the women in his life — estranged mother, lovers scorned, the ones who got away — fly in and out of focus, often standing in as metaphors for contemporary Chinese society and the forces of attraction and repulsion that underwrite the individual’s position within it. On “我老了,我哭了, 我恨你”, one of the album’s most poignant tracks, he could be speaking for himself or for an entire generation of post-’90s iconoclasts passed over by the long march of the new mainstream:

When it’s popular to be young, I’m old;

When it’s popular to smile, I cry;

When I should love you, I hate you.

In the final installment of our three-part interview, Dawei walks us through the themes of love, lust, history, and trauma that course through his debut album and accompanying video series, and hints at the shape his Gesamtkunstwerk will take moving forward…

pangbianr: Let’s talk about the work you have coming out now: the poetry book, the album, the DVD. What did you finish first, the book or the album?

Dawei: My album is an all-direction kind of output. My poetry book is a part of my album. Although my poetry book exists independently, to me it’s a link to the album.

pangbianr: “Shan Zhong Sun [山中孙]” is the first song you wrote, the night that you won the Nike battle, and it’s featured on the album. Can you talk a bit about it?

Dawei: Whenever I perform, I always perform that last, as my closing track. “Shan Zhong Sun” to me, compared to most of my other work now, is rather weak in language, in the way of thinking. But it was the first time I felt the power of rapping. All my work as a musician after “Shan Zhong Sun” is an enhanced version, all based on “Shan Zhong Sun.”

pangbianr: How do “Shan Zhong Sun” and the other ten songs on your debut album fit together? What’s the thematic connection?

Dawei: It’s the title of the album, Lust, Scars, The Insulted Man. Scars are all over lust, and lust is hidden within scars. Together, lust and scars attack me, turning me into the insulted man. It’s all connected. All the tracks on this album, they’re either talking about scars, which can mean scars from a certain time of life, or scars of the times we live in, or scars of history, of a specific historic time. Or, they’re about lust. These are the two themes representing the album.

pangbianr: In your work, these themes have a kind of dual meaning. They can have personal, literal meaning, and a meaning that’s historical, metaphorical. How do these motifs of “scars” and “lust” move between your personal story and your broader view of history or society?

Dawei: What is poetry? Poetry, I believe, is the art of metaphors. In this album, whenever I talk about sex, lust, or about suffering, I’m usually using them as metaphors. How I deal with something historical and something personal is that I turn them into something really vague. I take something general, historical, and take something personal, and mix them up, so you can’t see the edges. But it all seems really personal. Because the scars of the times are not abstract, they have a direct effect on me. Eventually they become my personal scars. Scars of the times and scars given by women, together they become my personal scars.

In other words, the suffering I get from history and the suffering I get from women are connected somehow. An artist interacts with the times he lives in, and with the history behind. That’s how he creates art. This kind of interaction can be gentle, and it can be violent, both mentally and physically. As a creator, the result of me interacting with the times and with history is my album. I see new scars growing on the old scars of the times, and upon the new scars comes a new order. And this new order makes the scars on me firmer and harder.

pangbianr: Let’s talk about some of the songs on the album. How about “我老了,我哭了,我恨你”? How does that song fit these themes?

Dawei: As the chorus says, “When it’s popular to be young, I’m old / When laughing is in fashion, I cry / When I’m supposed to have the courage to love you, I hate you.” On the surface, it seems like I’m talking about the pain I get from a woman, but deep down, it’s expressing the pain of being abandoned by the times, the pain of becoming a pariah. To keep failing to grasp the pulse of the times. The woman here is a metaphor for the times.

pangbianr: What about “杀人”?

Dawei: “杀人” is actually based one of my poems, “Brag (吹嘘)”. In the poem, there’s a figure of a weak lover hiding under the shell of a maniac, a madman like Hitler. In the lyrics, I talk about a lot of crazy thoughts, crazy ideas, such as, “I am the master that gives a woman her first orgasm / I am Hitler’s Adam’s apple dancing an empty dance.” I express these thoughts in the language of a maniac who is going in and out, going through the long history of the human race. But in the end I say, “I am a child’s innocence when I hold your hand / And I am sophistication when I let go.” That’s saying that my craziness, my mania, is about the fury that comes after being hurt, being abandoned, even though it’s very violent.

pangbianr: What about songs that are more abstract in their subject matter, like ”开开”?

Dawei: “开开”… What in the world are we really trying to open [kai, 开] here? I don’t know. One of the things that brings me a lot of anxiety now is that I don’t know what should be open any more. There are so many things that have been shut down, that have been closed, that we’ve lost sight of what we should open. What is left is the suffocation we get in the moment that we wake up every day. As the saying goes, “When God closes a door, he opens a window.” But in my eyes, God is the biggest opportunist.

In our times, every now and then people will feel so grateful that there are so many doors or windows open to them, but the truth is, it never comes at no cost. The invisible hand knows that if he closes all the doors, that’s death for everyone. That is death for us all. So after negotiation, he decides to open some in order to close others. But what is there now? Every now and then we feel, “Oh, there’s no air coming in.” But that makes us animals. It’s not enough to make us human beings. What I need is not a simple breeze, I need a shocking blizzard. So the doors and windows that have been closed and opened by the times and by women in my life, I want to open them all. I want to be a free man standing outside, even if it’s in an ice age.

Dawei with Cui Jian

pangbianr: You’ve closed a lot of doors to yourself by refusing to censor political and sexual content in your work. I want to ask about people who have gone out of their way to help you with your career. For example, how did Cui Jian first get in touch with or express interest in you?

Dawei: In a band that I used to jam with, the guy who played keyboard was friends with Cui Jian. For years, he’d been trying to find someone who could rap in Chinese, but he never found anyone. So when I became friends with this keyboardist, he showed Cui Jian a video of me battling. He was amazed. He said, “I have to meet him.” So that’s how we met.

pangbianr: It seems to me that he sees some artistic similarities between himself and you. How did your relationship develop? How has he supported your career?

Dawei: I think our relationship is more like brothers in the same kind of trouble than mentor and student. Patients in the same hospital. We share the same disease given by the times, given by women. Actually, I was inspired by Cui Jian to create this way of blurring the line between scars of the times and personal scars. Like turning time and history into the figures of women, and writing them countless love letters, challenge letters, death letters.

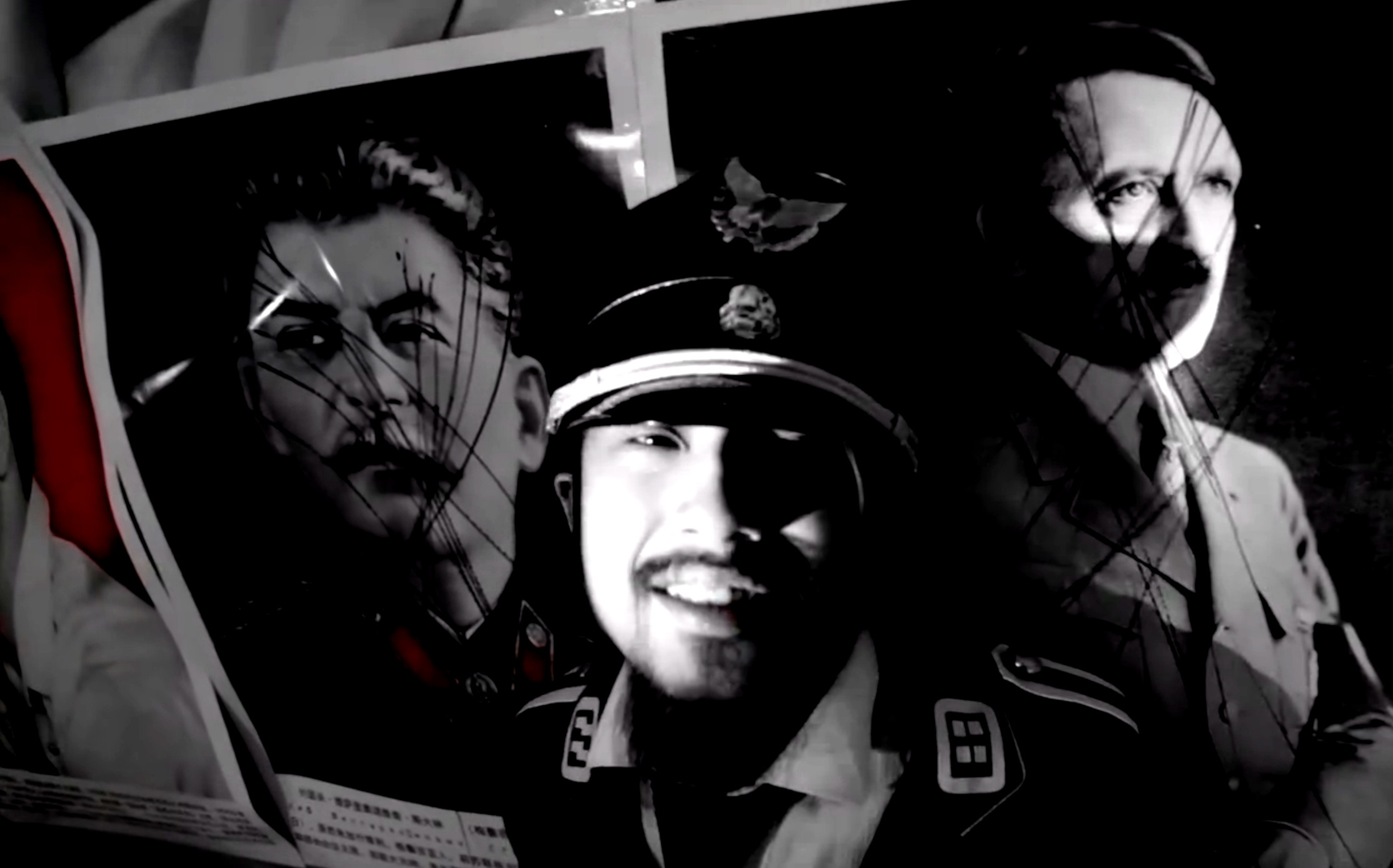

pangbianr: Your album is accompanied by a DVD of music videos that you conceptualized, directed, and acted in. How do these expand the music?

Dawei: A lot of my songs are explained and extended in my music videos. My music videos are like an instruction book for my music. For example, the music video for “Duwu Zhi Shang [独舞之殇]”. At the beginning, I’m a lonely man. Even though there’s a beautiful woman dancing in front of me, it’s as if I can’t see her. I’m focused on the beads in my hand. Two people are so close physically, but they’re so absorbed in their own worlds.

Dawei: In the next scene, it’s still the same man, but he’s tied up with bandages, rolled out in a wheelchair. He tries so hard to stand up on his feet, and when he does, he does the splits. From there begins the story of how he got insulted by different women, and the twisted plot and absurd stories between him and these women. After all those crazy stories, it’s the same man, in a wheelchair, tied up in bandages.

You can understand this in two ways. One: those stories actually happened, and led to his disability. Or, he’s always been this disabled man, and he played this all out in his head. Whether it’s the crazy drama between him and these women, or it’s him as a disabled man, on a wheelchair, alone, it’s always a one-man show. It’s always a person dancing alone.

Then there’s “Chuzhao Ba [出招吧]”, the martial arts video. It’s inspired by the Wong Kar-Wai movie The Grandmaster. It has three chapters. Nunchucks in the music video are a metaphor I use for lust. In the first chapter, I play nunchucks really slowly, with a woman by my side. We do it together. In the second chapter, I’m in an unknown space, surrounded by water. I play nunchucks alone in the water, hitting puddles, while recalling memories of being hurt and insulted by lust, by women.

Dawei: The third chapter portrays the conflict between me and this woman, and our individual conflicts with hypothetical rivals. This kind of conflict is psycho-sexual, but I present it in a physical way through martial arts, me versus my hypothetical rival. I picture him as a Japanese guy, we fight with samurai swords. My other imaginary rival made me fall in the water in a kung fu fight. When I’m making out with the woman, I imagine my rival is laying right next to me, in our bed, without anger, without criticism. When I propose to the woman, I propose with a flower, but I’m holding a knife behind my back.

The woman’s imaginary rival is played by me. She ties me up and feeds me food off the ground. So this imaginary rival symbolizes the bondage between me and this woman. The woman hates the rival, but also needs him. We keep cutting each other and drinking each other’s blood in these ongoing, actual and imaginary conflicts. Until the end, when the woman leaves me, and I kill myself. So in the end, I say, “We’re so in love, yet so far away from justice.”

These two along with “Shi Gui Ru Si [视归如死]” are my lust trilogy. In the first one, “Duwu Zhi Shang”, my frequent collaborator Sun Xiaoming is the lead actress, and she plays a supporting role in the second music video. She’s not even in the third video. The lead actress in “Chuzhao Ba” has the supporting role in “Shi Gui Ru Si”, the third one. So there’s this relationship between different faces.

Dawei: Scars become pedals here, pushing forward. In the first video, the main female character is the figure that brings me pain. In the second video, she’s fading away. In the first video, I use dance as a theme. In the second one, I use martial arts. In the third one, I’m mostly using the scenery, empty shots, or a man walking alone in the snow to express this kind of isolation.

So things get more intense, from “Duwu Zhi Shang” to “Chuzhao Ba”. The themes get intensified, sharpened. In the third one, it hits its peak, then cools down, turns into snow. The last scene of the video for “Shi Gui Ru Si” is a man disappearing in the snow, fading out. Where is he going? We don’t know. But it’s very likely that he goes back to repeating himself, creating another lust adventure like the first two music videos. This is why I have to put my poetry, my music, and my music videos in the same box. They’re each other’s extensions and explanations.

pangbianr: I know you’re working on an original short film now, can you talk about that? What is it about? Why do you want to make a film outside of the context of music videos?

Dawei: Sure I can talk about it, but I won’t tell you the actual story of the movie. All I’ll say is that it’s a story about how everyone is responsible for STD prevention, and how revolution is a crime and rebellion is not justified. Time is violently crushed by me in this movie. An old Soviet dream? The aftermath of a run-in with Big Brother? CCTV News? The commerce of love? That’s all I’ll say. As for why I’m making a movie… I woke up one day shocked to find my poetry stirring inside of me, no longer satisfied with only abstract puzzles and imagery. It’s demanding stories from me. I could do nothing but satisfy it.

pangbianr: Now that Lust, Scars, The Insulted Man is out, what’s next for you? What are your plans for 2016 and beyond?

Dawei: Right now I have a new poetry book, a new movie, two new albums, a book of impressionistic historical fiction, and a book of short stories in progress… so many things.

***

Dawei has just released Lust, Scars, The Insulted Man, a box set containing a CD, a DVD of self-directed music videos, and a book of his poetry. Stream it here and buy it here. Read Parts I & II of this interview here:

*This interview was conducted in Chinese and translated to English by Emma Sun