Zully Adler Interview

By Josh, 2012年 1月 20日

In my 2011 year-end list, I highlighted a Soviet Pop cassette released by US-based DIY label Goaty Tapes. The brain behind this operation is one Zully Adler, who started the label in high school to become involved in his local Los Angeles music scene and has pursued it as both a personal journey of music discovery and a platform to connect with like-minded DIY-ers around the globe. Zully is currently on a Watson Fellowship, a one-year grant which has allowed him to document DIY music scenes in Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, and now Beijing.

Since arriving, Zully has made the rounds, seeing every band he can at shows, practice rooms, studios, et al. We sat down for this short interview during a Chui Wan apartment mixing session. Read on to learn more about Zully’s philosophy behind making tapes, the unique energies he’s zeroed in on in Beijing, and some of the most interesting lessons he’s learned so far on his trip around the world. And if you’re free (and still in town) on Friday, January 20th, stop by Hot Cat Club for a free show featuring Zully’s one-man-band Banana Head along with Soviet Pop and Luxinpei.

Banana Head live in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

pangbianr: First, I want to introduce your label Goaty Tapes, which recently released a tape from the Beijing band Soviet Pop, and before that a tape from Simon Frank [of Hot & Cold], who has a pretty strong Beijing connection. Can you talk a little bit about your philosophy for the label and the concept behind it? Besides China, you’ve also released artists from Germany and Russia. How do you go about finding interesting international bands?

Zully Adler: Well the label started when I was in high school, I think I was 16 or 17. It was originally a way of getting involved in the local music scene in Los Angeles. Over the years it expanded to include any and all artists that I was interested in who would be generous enough with their music to contribute. There was really no prescribed aesthetic or genre for the label, but I am generally attracted to music that has a more intimate quality to it, and that usually comes across in the way the music is recorded. So a band like Soviet Pop that records their music live with a room mic, like they did for the release that we worked on together, fits into the general intimacy of the label that I’ve tried to foster over the years. And that comes across in the way that I send out newsletters and correspond with bands and people who buy from my website. I even advertise the fact that my mom handles my mail order when I’m away. So it’s about fostering that individuality and breaking down the barriers that are created when you start distributing music on the internet. Most of the releases can be described as “lo-fi” or “damaged”, but I think that also fits in with the idea of intimacy because there’s a certain naiveté, or an experimental or child-like approach that a lot of bands take when they play music. It’s less about developing virtuosity as a musician and more about expressing yourself despite the fact that you might not know how to play your instrument.

Soviet Pop – “Sound of Sweat Radio”

Beyond that, the label really functions doubly as an art project for me. I always liked making cover art or making art in general, and tapes as a medium offer a lot of different surfaces for design and for packaging. That said, I don’t do wild or outlandish packaging because I don’t like the burden of having to find a special place for the tape, I like it to fit snugly with the rest of somebody’s tape collection. Even if some crazy big poster packaging looks cool, it’s like, “…where do I put it?”, you know?

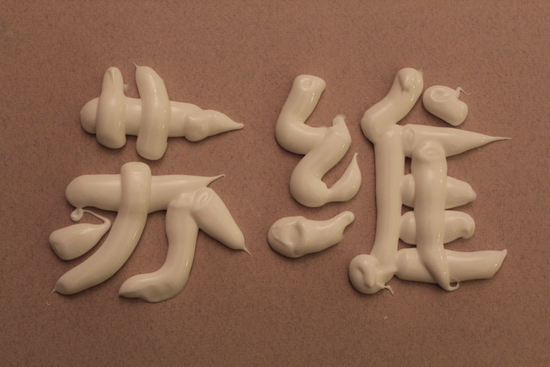

Soviet Pop tape packaging

“Soviet” transliterated in Chinese/toothpaste

I guess over the years I’ve moved away from wildly experimental or improvised music and into more subtly song-based or structured music. Even with the songs I worked on with Soviet Pop, they asked me if I wanted more experimental stuff or what they call their “pop” music, and I chose the pop stuff because I thought that almost had a more subversive edge to it. When there is a beat or there’s a semblance of a beat, a semblance of song structure, your expectations are undermined by the damaged or experimental quality of the music that almost kind of hints at pop or rock. So, I guess that’s how Goaty Tapes has functioned thus far, but it’s susceptible to change. I didn’t define the project when I started and I hope it continues to develop in new and different ways.

pbr: How did you initially get turned on to the Chinese scene? I assume your first contact was with Simon? How did putting out his tape lead to you collaborating with Soviet Pop and then becoming interested in enough in Beijing to actually come out here?

Zully: I found Simon on the internet, through certain music connections that I had made that brought me closer to the Toronto scene. I’d previously been in touch with Frank who runs the Hobo Cult label because we did a tape together of his band Death Light. Through Frank I found Simon, we worked on a project together. I love Simon’s music. When I heard that he was corresponding pretty regularly with these Chinese bands and had spent some time [in Beijing], I was intrigued because it was a big chunk of the world that had yet been unexplored under Goaty’s auspices. I felt like talking to Simon about bands in Beijing would be a good opportunity to explore what was available.

Simon Frank – “Unheated Neighbors” CS

He sent me a bunch of links and I looked into some local bands, and I was really taken aback by the quality – not necessarily the quantity, but just the quality of the music that was coming out of Beijing. In the past three months I’ve been across a lot of countries in Asia, and some of them have extremely vibrant DIY music communities, but none have the forward-thinking progressive element that I find in Beijing. A lot of them play pretty traditional punk and metal. Whether it’s ’76 punk or black metal, I can still listen to it and almost immediately fit it into a genre that I’ve already come across. Whereas when I heard Soviet Pop, I didn’t know quite what to think. And that’s been the driving impulse of putting out tapes for me. If I hear something and I can’t immediately define what it is or where it came from, I’m much much more inclined to get in touch with the artist and to work with them.

So at that point I knew very little about Beijing or Chinese music in general. I had a general interest in China because I come from a Marxist family… actually, my grandmother on my father’s side was the Communist cultural liaison between Australia and Maoist China. I don’t really have political allegiances to any of that in particular, but it made the connection a little stronger for me.

pbr: You’re on a traveling grant now, basically going to a lot of under-explored music scenes around the world — places like Southeast Asia, Australia, and now Beijing — to study tape culture and DIY culture. What is your goal? What are you trying or hoping to find? What have you actually found? What are some of the stand-out scenes or bands that you’ve seen?

Zully: Basically the idea of the trip is to explore how and why people produce and distribute their own music. I’m interested in the trade-based network that musicians create through the independent creation of their music releases. Specifically, I want to know how it takes the form of the cassette because it’s such an odd medium to use these days. But I haven’t excluded [web] labels or CDRs, vinyl, anything really.

What’s been interesting to trace are the obstacles that different artists face under different governments, under different cultural paradigms… Beijing in particular, it’s been interesting to note, faces a lot more in terms of censorship when it comes to distributing their own music. This trip has really more than anything expanded my definition of what it means to be “DIY” and make your own music. That way that I understood it, and I think a lot of people understand it, was as a fairly recent phenomenon that is in reaction against a commercial music industry. But what I’ve come to learn is that there’s a much longer arc that connects these DIY movements to independent music that’s been going on for 40, 50, 60… 80 years, even. Especially in Indonesia, where I came across a lot of traditional bands of these ancient musicians in their 70s and 80s who were still making and distributing their own music, whether it was on tape or cd, or even on the internet in some cases, which was the most interesting because, I mean, I know my grandpa doesn’t know how to use the internet… That was definitely one of the more mind-expanding parts of this trip, was kind of re-defining the idea of DIY in light of the fact that there are people who do it under all sorts of circumstances.

Tropic tape duplication, Bandung, Java, Indonesia

In America, because people have access to other ways of doing their music and there is a relatively large commercial sphere, you specifically decide to release your music independently. But in some of these other places, I met a lot of people that just had no choice but to distribute their music on cassette. I worked with a punk collective called Alternaive in Bandung [Indonesia], and they didn’t own laptops or computers so they couldn’t distribute their music very effectively on the internet. They could only do it with physical releases. Not only that, but the one place left in Bandung that would duplicate releases is called Tropic CDR and Tape. At Tropic, the lowest run for a CD release is 1,000, whereas the lowest run for a tape is 50. These guys clearly did not have the capital to invest in a thousand CDs, let alone sell those CDs. So tapes are really the only option available to them. That was really interesting to encounter, because that doesn’t happen in the United States.

Deden of Alternaive DIY collective, Bandung, Java, Indonesia

It’s interesting to note how this is in some ways not a reaction against commercial music, but a solution to the demise of commercial music. As it becomes more and more difficult to sell music on a large scale, these big companies disintegrate and it’s up to the bands themselves to figure out how they want to produce and distribute their music.

pbr: Since you’ve been in Beijing, you’ve been able to see a few shows and have met a lot of musicians. What is your sense of the city? What do you think are the most interesting aspects of the Beijing music scene from the small window you’ve had on it so far?

Zully: One thing that’s interesting is that there’s this strange… I don’t know if it’s a duality or a dialectic… there seems to be a lot of different scenes within Beijing, but at the same time each scene seems very inclusive. So, even though there are enough people to have a folk scene, and a metal scene, a punk scene and an experimental scene, even within each of those you have people that expand the definition of those genres and create these gray areas between genres or between communities. That’s one thing that’s been interesting to note. And I guess the positivity and receptivity of a lot of the musicians and promoters that I’ve encountered here… nothing is denounced just because it belongs to a different group or has a different sound. Things are considered in terms of their irreducible singularity, and people want to know that person as an individual before they make any claims about them.

I think I came at a strange time during the year in China, but I’ve been glad to catch a lot of the people that I would like to see. I’d like to extend a thank you to everyone I’ve met because they’ve all been very hospitable to me, welcoming and helpful in negotiating the music scene in Beijing.

buy Goaty Tapes: goatytapes.com

follow Zully’s travels: GlobalDIY.blogspot.com

Awesome